Questions and answers on tobacco use, including waterpipe use and COVID19 in the Eastern Mediterranean Regioni

What are the possible relations between tobacco use and the COVID19 epidemic?

Any kind of tobacco smoking is harmful tothe bodily systems, includingthe cardiovascular and respiratory systems[1][2]. COVID-19 can also harm these systems. Information fromChina, where COVID-19 originated, shows that people who have cardiovascular and respiratory conditions caused by tobacco use, or otherwise,are at higher risk of developingsevere COVID-19 symptoms[3]. Research on 55,924 laboratory confirmed cases in China shows that the crude fatality ratiofor COVID-19 patients is much higher among those with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, chronic respiratory disease or cancer than those with no pre-existing chronic medical conditions[4]. Thisdemonstratesthat these pre-existing conditions may contribute to increasingthe susceptibility of such individuals to Covid-19.

Tobacco has a huge impact on respiratory health. The link between tobacco use and lung cancer is well-established, with tobacco use beingthe most common cause of lung cancer[5]. It alsosubstantially increases the risk of tuberculosis infection[6]. Further, tobacco use is also the most important risk-factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), causing the swelling and rupturing of the air sacs inthe lungs, which reduces the lung’s capacity to take in oxygen and expel carbon dioxide, and the build-up of mucus, which results in painful coughing and breathing difficulties[7][8][9]. This may have implications for smokers, given thatsmoking is considered to be a risk factor for any lower respiratory tract infection[10]and the virus that causes COVID-19 primarily affects the respiratory system,often causing mild to severe respiratory 2damage[4]. However, given that COVID-19 is a newly identified disease, thelink between tobacco smoking and the diseasehas yet to be established.

There isan increased risk of more serious symptoms and death among COVID-19 patients that have underlying cardiovascular diseases (CVDs)[11][12]. According to the available evidence the virus that causesCOVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) is from the same family as MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, both of whichhave been associated with cardiovascular damage (either acute or chronic) [13][14]. Research has shown COVID-19 patients in China with CVDs are at greater riskof more severe symptoms[15]In addition, there is evidence that COVID-19 patients that have more severe symptoms often have heart related complications[16].This relation between COVID-19 and cardiovascular health is important because tobacco use and exposure to second-hand smoke are major causes of CVDs globally[17]. The effect of COVID-19 on the cardiovascular system could thus make pre-existing cardiovascular conditions worse. In addition, a weaker cardiovascular system among COVID-19 patients witha history of tobacco use could make such patientssusceptible tosevere symptoms,therebyincreasingthe chance of death[18].

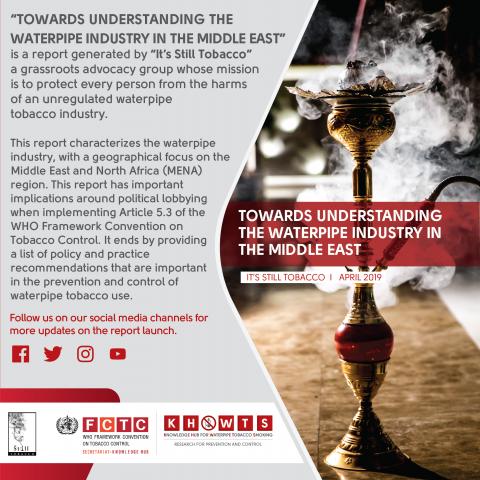

How can use of waterpipe contribute to the spread of COVID19?

Waterpipes aretobacco products [19]and their use has both acute and long-term harmful effects on the respiratory and cardiovascular systems [20], likely increasing the risk of diseases including coronary artery disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[21].

The communal nature of waterpipe smoking means that a single mouthpiece and hose areoftenshared between people, especially in social and communal settings[22]. In addition, the waterpipe apparatus (including the hose and chamber) itself may contribute to this risk by providing an environment that promotes the survival of microorganisms outside the body. Most cafés tend not to clean the waterpipes after each smoking session because washing and cleaning waterpipe parts is labour intensive and time consuming[23][24].These factorsincrease the potential for the transmission of infectious diseases between users[20].Consistent with this, evidence has shown that waterpipe use is associated with an increased risk of transmission of infectious agents such as respiratory viruses, hepatitis C virus, Epstein Barrvirus, Herpes Simplex virus, tuberculosis, Heliobacter pylori, and Aspergillus[25][26][27][28][29][30]. Social gatherings provide ample opportunityfor the virus that causes COVID-19 to spread [31].

Since waterpipe smoking is typically an activity that takes place within groups in public settings[22]andwaterpipe use increasesthe risk oftransmission of diseases, it could also encourage the transmission of COVID-19 insocial gatherings. When this smoking takes place in indoor areas, as it does in many places, the risk could be higher.

Will strengthened tobacco control measures help in this context?

In 2008, WHO introduced theMPOWER technical package,which is based on key tobacco demand reduction articles of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC),as follows:

- Monitor tobacco use and prevention policies

- Protect people from tobacco use

- Offer help to quit tobacco use

- Warn about the dangers of tobacco

- Enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship

- Raise taxes on tobacco.

Strengthened tobacco control measures including tobacco free public places and protection of people from second hand smoke as per the WHO FCTC Article 8 and its Guidelines will reducethe risk of suffering from severesymptoms. Lower tobacco use will reduce rates of many respiratory and cardiovascular conditions that are strongly associated with more serious COVID-19 symptoms and mortality.

Reducing the demand for tobacco products, including waterpipe, could also indirectly discourage the social gatherings that contribute to the spread of the virus.ú

Good respiratory and cardiovascular health is important for a COVID-19 patient topositivelyrespond and successfully recover from the disease.

Specifically regarding waterpipe usage, since it is often overlookedin tobacco control efforts, there is a significant opportunity for positive health outcomes at this time, both with respect to COVID-19 and generally, if immediate comprehensive tobacco control measures are takenthat include the control of waterpipe.

Countries can use the WHO’s highly effective MPOWER policy package to support their formulation and implementation of tobacco control measures.

How can regional tobacco control legislation support the limitation of the virus spreading?

The same considerations thatapply to tobacco control globally as per the WHO FCTC and the MPOWER policy packagealso apply to tobacco control within the Eastern MediterraneanRegion (EMR). Countries should seek to limit the use of waterpipe and other tobacco use in order to reduce its well documented health impactand improve people’s respiratory and cardiovascular health.

Controlling tobaccouse and reducing waterpipe usemay be important for reducing the risk of the transmission of the virus that causes COVID-19.It is important that the control of waterpipe use is taken especially seriously at this timeand within a comprehensive approach to control all tobaccouse in light of WHO FCTC obligations and MPOWER policy recommendations.

In general, WHO recommends that countries fully implementthe WHO FCTC and the MPOWER policy package.This includes a comprehensive ban onall forms of tobacco use,includingwaterpipe, in all public places (incl. cafes and restaurants).Such a ban may help prevent anyincreased risk of transmission of the virus that causes COVID-19 that may be related to tobacco use. Countries should ensure that this ban is fully enforced.

Why is this a good time to try and quit tobacco use?

Tobacco use dramatically increases the risk of many serious health problems, including both respiratory problems (like lung cancer, TB and COPD) and cardiovascular diseases. While this means that it is always a good idea to quit tobacco use, quitting tobacco use may be especially important at this time to reduce the harm caused by COVID-19.Tobacco users areprobably less likely to become infected if they quit because the absence of smoking helps reduce the touching of fingers to the mouth. Also, it is possible that they would better manage the comorbid conditionsifthey become infectedbecause quitting tobacco use has an almost immediate positive impact on lung and cardiovascular function and these improvements only increase as time goes on[10]. Such improvement may increase the ability of COVID-19 patients to respond to the 5infection and reduce the risk of death. Faster recovery and milder symptoms also reduce the risk of the transmission of the disease to other people.

What are the key lessons learnt from previous experiences?

From previous experience in responding to MERS-Cov and SARS-CoV, general precautions should be taken,especially in social gatherings[31].

Waterpipes may bea catalyst for social gatherings in environments thatcould increase disease transmission.

Previous evidence showsthatsmoking has adverse effects on the survival of individuals with infectious diseases[32]and evidence from otheroutbreaks caused by viruses from the same family as COVID-19 suggeststhat tobacco smoking could, directly or indirectly, contribute to an increased risk ofinfection,poor prognosis and/or mortality for infectious respiratory diseases[33][34].

What is next??

This document is based on the most updated available evidence.

Evidence is still evolving and the document will be subject to updates in light of any new emerging evidence. Regularlywe will look into the new available evidence and update the document.

In the context of COVID19 countries are encouraged to take the needed action to protect the public from the devastating health consequences of tobacco use in light of their international commitments under the WHO FCTC and WHO recommendations.

References

[1] World Health Organization, World Heart Federation, Cardiovascular harms from tobacco use and secondhand smoke: Global gaps in awareness and implications for action, Waterloo, Ontario, Geneva, 2012.

[2] World Health Organization, World No Tobacco Day 2018: Tobacco breaks hearts -choose health. not tobacco, Geneva, 2018.

[3] W.-j. Guan, Z.-y. Ni, Y. Hu, W.-h. Liang, C.-q. Ou, J.-x. He, L. Liu, H. Shan, C.-l. Lei, D. S. Hui, B. Du, L.-j. Li, G. Zeng, K.-Y. Yuen, R.-c. Chen, C.-l. Tang, T. Wang, P.-y. Chen, J. Xiang, S.-y. Li, J.-l. Wang, Z.-j. Liang, Y.-x. Peng, L. Wei, Y. Liu, Y.-h. Hu, P. Peng, J.-m. Wang, J.-y. Liu, Z. Chen, G. Li, Z.-j. Zheng, S.-q. Qiu, J. Luo, C.-j. Ye, S.-y. Zhu and N.-s. Zhong, “Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China,” New England Journal of Medicine, 2020.

[4] World Health Organization, Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), 14-20 Februray 2020., 2020.

[5] F. Bray, J. Ferlay, I. Soerjomataram, R. L. Siegel, L. A.Torre and A. Jemal, “Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries,” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, vol. 68, no. 6, pp. 394-424, 2018.

[6] K. Lönnroth and M. Raviglione, “Global Epidemiology of Tuberculosis: Prospects for Control,” Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 481-491, 2008.

[7] N. Terzikhan, K. M. C. Verhamme, A. Hofman, B. H. Stricker, G. G. Brusselle and L. Lahousse, “Prevalence and incidence of COPD in smokers and non-smokers: the Rotterdam Study,” European Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 31, no. 8, pp. 785-792, 2016.

[8] Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, “GBD Compare | IHME Viz Hub,” [Online]. Available: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare. [Accessed 12 03 2020].

[9] C. Janson, G. Marks, S. Buist, L. Gnatiuc, T. Gislason, M. A. McBurnie, R. Nielsen, M. Studnicka, B. Toelle, B. Benediktsdottir and P. Burney, “The impact of COPD on health status: findings from the BOLD study,” European Respiratory Journal, vol. 42, no. 6, pp. 1472-1483, 2013.

[10] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, The health consequences of smoking: 50 years of progress -A report by the Surgeon General, Atlanta, 2014.

[11] C. Huang, Y. Wang, X. Li, L. Ren, J. Zhao, Y. Hu, L. Zhang, G. Fan, J. Xu, X. Gu, Z. Cheng, T. Yu, J. Xia, Y. Wei, W. Wu, X. Xie, W. Yin, H. Li, M. Liu, Y. Xiao, H. Gao, L. Guo, J. Xie, G. Wang, R. Jiang, Z. Gao, Q. Jin, J. Wang and B. Cao, “Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China,” The Lancet, vol. 395, no. 10223, pp. 497-506, 2020.

[12] Y.-Y. Zheng, Y.-T. Ma, J.-Y. Zhang and X. Xie, “COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system,” Nature Reviews Cardiology, 2020.

[13] T. Alhogbani, “Acute myocarditis associated with novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus,” Annals of Saudi Medicine, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 78-80, 2016.

[14] Q. Wu, L. Zhou, X. Sun, Z. Yan, C. Hu, J. Wu, L. Xu, X. Li, H. Liu, P. Yin, K. Li, J. Zhao, Y. Li, X. Wang, Y. Li, Q. Zhang, G. Xu and H. Chen, “Altered Lipid Metabolism in Recovered SARS Patients Twelve Years after Infection,” Scientific Reports, vol. 7, no. 1, 2017.

[15] Q. Ruan, K. Yang, W. Wang, L. Jiang and J. Song, “Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China,” Intensive Care Medicine.

[16] D. Wang, B. Hu, C. Hu, F. Zhu, X. Liu, J. Zhang, B. Wang, H. Xiang, Z. Cheng, Y. Xiong, Y. Zhao, Y. Li, X. Wang and Z. Peng, “Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China,” Journal of the American Medical Association, 2020.

[17] Global Burden of Disease 2018 Risk Factor Collaborators, Institute for HealthMetrics and Evaluation, “Global, regional and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis,” 2018.

[18] The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team, “The Epidemiological Characteristics of an Outbreak of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) -China, 2020,” China CDC Weekly, vol. 2 , no. 8, 2020.

[19] World Health Organization, Factsheet: Waterpipe smoking and health, 2015.

[20] WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation, Waterpipe tobacco smoking: health effects, research needs and recommended actions for regulators (2nd ed.), 2015.

[21] Z. El-Zaatari, H. Chami and G. Zaatari, “Health effects associated with waterpipe smoking,” Tobacco Control, vol. 24, no. Suppl 1, pp.31-43, 2015.

[22] W. Maziak, Z. Taleb, R. Bahelah, F. Islam, R. Jaber, R. Auf and R. Salloum, “The global epidemiology of waterpipe smoking,” Tobacco Control, vol. 24, no. Suppl 1, pp. 3-12, 2015.

[23] P. Koul, M. Hajni, M. Sheikh, U. Khan, A. Shah,Y. Khan, A. Ahanger and R. Tasleem, “Hookah smoking and lung cancer in the Kashmir valley of the Indian subcontinent,” Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 519-24, 2011.

[24] K. Daniels and N. Roman, “A descriptive study of the perceptions and behaviors of waterpipe use by university students in the Western Cape, South Africa,” Tobacco Induced Diseases, vol. 11, no. 1, 2013.

[25] J. Urkin, R. Ochaion and A. Peleg, “Hubble bubble equals trouble: the hazards of water pipe smoking,” Scientific World Journal, vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 1990-7, 2006.

[26] W. Munckhof, A. Konstantinos , M. Wamsley, M. Mortlock and C. Gilpin, “A cluster of tuberculosis associated with use of marijuana water pipe,” Internation Journal of Tuberculosis andLung Disease, vol. 7, no. 9, pp. 860-5, 2003.

[27] M. El-Barrawy, M. Morad and M. Gaber, “Role of Helicobacter pylori in the genesis of gastric ulcerations among smokers and nonsmokers,” Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal , no. 3, pp. 316-21, 1997.

[28] M. Habib, M. Mohammed, F. Abdel-Aziz, L. Magder,M. Abdel-Hamid, F. Gamil, S. Madkour, N. Mikhail, W. Anwar, G. Strickland, A. Fix and I. Sallam, “Hepatitis C virus infection in a community in the Nile Delta: risk factors for seropositivity,” Hepatology, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 248-53, 2001.

[29] B. Knishkowy and Y. Amitai, “Water-pipe (narghile) smoking: an emerging health risk behavior,” Pediatrics, vol. 116, no. 1, pp. 113-9, 2005.

[30] M. Szyper-Kravitz, R. Lang, Y. Manor and M. Lahav, “Early invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in a leukemia patient linked to aspergillus contaminated marijuana smoking,” Leukemia & Lymphoma, vol. 42, no. 6, pp. 1433-7, 2001.

[31] US Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention, Implementation of Mitigation Strategies for Communities with local COVID-19 Transmission, 2020.

[32] R. Huttunen, T. Heikkinen and J. Syrjanen, “Smoking and the outcome of infection,” Journal of Internal Medicine, vol. 269, no. 3,pp. 258-269, 2010.

[33] L. Seys, W. Widago, F. Verhamme, A. Kleinjan, W. Janssens, G. Joos, K. Bracke, B. Haagmans and G. Brusselle, “DPP4, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Receptor, is Upregulated in Lungs of Smokers and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 6, no. 66, pp. 45-53, 2018.

[34] B. Alraddadi, J. Watson, A. Almarashi, G. Abdei, A. Turkistani, M. Sadran, A. Housa, M. Almazroa, N. Alraihan, A. Banjar, E. Albalawi, H. Alhindi, A. Choudhry, J. Meiman, M. Paczkowski, A. Curns, A. Mounts, D. Feikin, N. Marano, D. Swerdlow, S. Gerber, R. Hajjeh and T. Madani, “Risk Factors for Primary Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Illness in Humans, Saudi Arabia, 2014,” Emerging infectious diseases, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 49-55, 2016.

[35] World Health Organisation, 13th Global Programme of Work: WHO Impact Framework, 2019.

[36] W. Liu, Z.-W. Tao, W. Lei, Y. Ming-Li, L. Kui, Z. Ling, W. Shuang, D. Yan, L. Jing, H.-G. Liu, Y. Ming and H. Yi, “Analysis of factors associated with disease outcomes in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease,” Chinese Medical Journal, 2020.

i Note: Many countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region have reported cases of COVID-19. The WHO is actively involved in supporting Member States prepare and respond to the outbreak. Further regularly updated information about COVID-19 and the WHO’s work can be found here: http://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/corona-virus/index.html

For information on countries that took action to strengthen tobacco control in light of COVID19 please contactTobacco Free Initiate WHO EMRO emrgotfi@who.int

(please Check the link below)

Share